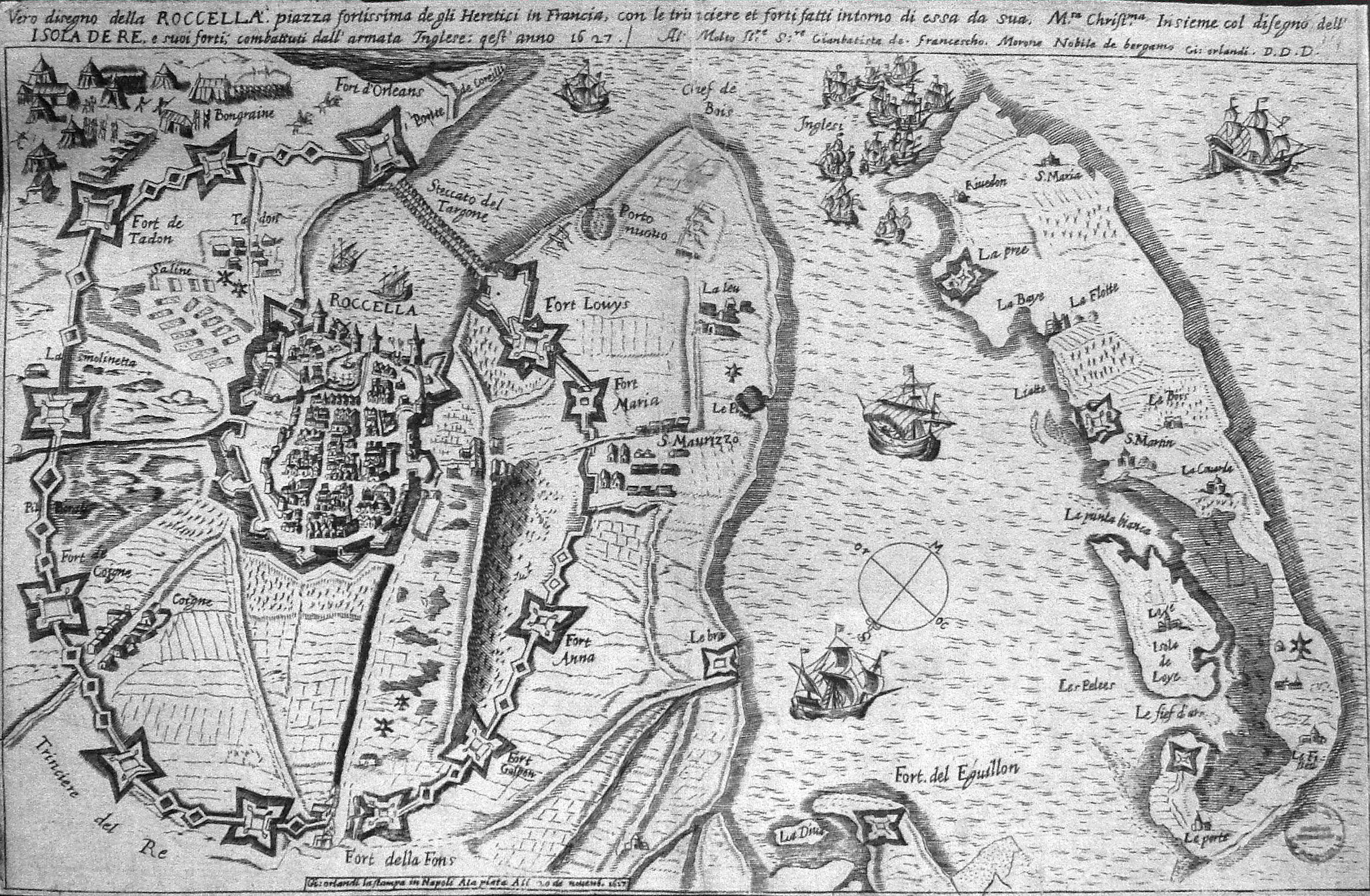

Siege of La Rochelle, with nearby Île de Ré, by G.Orlandi, 1627.

An important, perhaps to the participants even the key, feature of Early Modern were sieges. It is true in all times and all places that soldiers spend very little of there actual time engaged in battle, especially big, clash of armies battles. Hence the aphorism that war is -

Months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror.

A lot of a soldier's time is spent waiting and trying to stave off the boredom of having to wait. And in early modern warfare some significant time periods were spent waiting on one side or the other of a siege line. Sieges could last for years:

- Ostend (1601–04)

- Breda (1624 – 1625)

- La Rochelle (1627–1628)

- Mantua (1629–30)

- Casale Monferrato (1629–31)

- Candia (Crete) (1648–69) Yeah that’s right that's twice as long as the legendary 10 year siege of Troy.

- Waterford (1649-1650)

- Copenhagen (1658–1659)

- Fort Zeelandia (1661–1662)

- Ceuta (1694–1727) - 33 years! Claimed as the longest siege in history.

Our post Blitzkrieg, post Shock & Awe modern military viewpoint has a lot of difficulty comprehending the importance and focus that siege warfare and fortification design held on 17th century military and political thinkers and decision makers. Indeed we have a lot of trouble understanding the thought processes of the General Staff on either side in the First World War or the French over reliance on the Maginot line that followed it.

Capturing strong points was important to the way political and military leaders conceptualized war and its aims. And for the noble classes who provided most of the officers in the armies of the period, war was a way to gain glory and renown. And with the exception of a one army smashing into another sort of big battle - which only happened rarely in that or most periods, a successful conducted siege - whether as the besieger or the defender was likely to result in glory and promotions for some of the officers. And for the besiegers there might even be the bonus of a chance to loot the town.

Capturing strong points was important to the way political and military leaders conceptualized war and its aims. And for the noble classes who provided most of the officers in the armies of the period, war was a way to gain glory and renown. And with the exception of a one army smashing into another sort of big battle - which only happened rarely in that or most periods, a successful conducted siege - whether as the besieger or the defender was likely to result in glory and promotions for some of the officers. And for the besiegers there might even be the bonus of a chance to loot the town.

"The origins of the great transformations of the 18th and 19th centuries

(the Enlightenment, and the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions) are

firmly in the 17th century. The transformation on the battlefield was no less dramatic –

military engineering which was regarded as an ‘art’ during the 16th

century was very much a science by the end of the 17th ..."

Siege warfare with on one side the immense precisely designed star-shaped fortifications on the one side and the geometric traceries of multiple circumvallations connected by parallel communication trenches on the other is the aspect of warfare most amenable to the new fascination with reason and science. And the acknowledged master of the period was Vauban.

"Civil War sieges fall into four types:

- The coup de main, where surprise was used (such as Alexander Leslie’s capture of Edinburgh Castle in 1639).

- The ‘smash and grab', where an assault was launched after a preliminary bombardment, a preferred tactic of the New Model Army (and on at least one occasion, at Dartmouth Castle in 1646, the assault was launched without any bombardment). Here, just the threat of the assault was often enough to persuade the garrison to surrender.

- The blockade, which was a longer-lasting affair, and the besieger invested the place of strength, preventing communication and offensive activities by the garrison. This was the preferred option by an attacker unwilling (or unable) to attempt an assault and was used (without much success) by the Royalists at Gloucester, Plymouth and Lyme Regis.

- Finally, and quite uncommon was the complete investiture, where a circumvallation of rampart and ditch, fort and battery would be constructed around the entire town, in so doing cutting it off from the outside world. Examples of this are few: Newark (1645-6), Oxford (1646) and Colchester (1648)."

Cardinal Richelieu at the Siege of La Rochelle, Henri Motte, 1881.

These same categories are prevalent in nearly all military periods. Any of these types could be rich fodder for an RPG. Note that here I am not contemplating an RPG where the players are running the characters who are commanding the opposing armies or major units. That situation is closer to the typical wargaming session than it is to the typical RPG session. And if all the players are up for that the appeal should be obvious. Instead lets look at the more common situation where the PCs do not control major military units. So how does the GM use these situations? Let's look at them one by one.

- The traditional OD&D dungeon crawl is an example of a coup de main. And it points the way towards how to use the PCs. Obviously they, with their mad skillz and willingness to take insane risks at the drop of a gold piece are invaluable for a surprise assault.

- The 'smash and grab' also sounds like a traditional dungeon crawl, but arguably the preliminary bombardment may differentiate the two. Though clearly these two categories overlap as Flintham acknowledges when he mentions that the assault on Dartmouth Castle was launched without any bombardment. And presumably the assault on Dartmouth came as a surprise to defenders who, once the saw the besieging army march on up to their walls, were probably expecting the traditional bombardment prior to an assault. The PCs are perfect for the quintessentially forlorn hope that leads the assault. And if your game is one that features powerful magic users (like many versions of D&D) why your PCs are also the artillery for the initial bombardment of the 'smash and grab.' And don't forget the defenders. Most fortifications have a few key areas and a few key vulnerabilities. Put the PCs there defending the important redoubt or holding the gateway once the ram has battered it down.

- The blockade is probably the least used type for RPGs, with the possible exception of naval and sci-fi based RPGs. The blockade and on its other side the blockade runner (you know that ship that we see at the beginning of A New Hope and the end of Rogue One). In part I suspect that is because blockade duty, like a complete investiture, is boring most of the time, but it lacks the fun of siege engines and the pageantry of one army staring at the other across their fortress walls and encircling circumvallations. As mentioned, crashing the blockade is probably the easiest and most natural use for PCs. For naval blockades it does require that the PCs have a ship and for land blockades they should be mounted rather than infantry.

- The complete investiture has some of the same aspects as the blockade. We may see the defenders sending for help like we see, unsuccessfully, in Last of the Mohicans. PCs are perfect for this role. Otherwise I think that the investiture is best used as a backdrop. It may be the starting point for an assault or escalade (ascent by rope or ladders) which defaults to either the coup de main for, say a night escalade, or to the 'smash and grab' for an attack on a breach in the wall or a day time assault under covering fire. Another way to use the full investiture type of siege is assign the PCs to special forces or commando roles. They may be tasked to special missions to: sabotage an enemy battery, capture or kill an enemy leader, poison the water supply, blow up the ammo dump, set fires, drop the drawbridge and jam the portcullis, etc. I used several of the special missions during an arc where I set the PCs inside the town of Bergen-op-Zoom during the Spanish siege. Their roles included counter espionage, foiling attempts to blow up the towns powder magazine or to poison wells, stopping terror attacks aimed at destroying civilian will, holding important strong points against vigorous assault, and launching harassing raids to sabotage enemy guns or destroy the attackers morale.

- Flintham left out one more way to take a fortress - treason. This too is good fodder for the PCs and it allows more scope for the more talkative and intellectual PCs and players beyond simply killing everything in their path. Figuring out how to find a weak defender who is susceptible to bribery or threats on the one hand or, for the defender, trying to catch the attacker's saboteurs and agents provocateur before they can strike on the other.

No comments:

Post a Comment